Space Foundation News

How Satellites are Fighting Coronavirus … from Space

Written by: Andrew de Naray

Images of the coronavirus commonly seen on the web have been magnified as many as 40,000 times. In fact, coronavirus microbes are so tiny, it would take 1,000 of them to span the width of an eyelash. So, it may seem paradoxical that beyond closely analyzing the coronavirus in labs, we are also observing its effects on humanity from much, much farther away than the advised social distancing of six feet … actually, from low

Earth orbit.

Pre-pandemic, most of us already knew that satellites provide global positioning data that helps us easily navigate to the hot new restaurant in town. But satellite pictures of vacant tourist attractions sprinkled throughout the news media since coronavirus swept the globe are beginning to raise awareness about the powerful capabilities of Earth observation. And although seeing images of major tourist attractions devoid of visitors is impactful, there’s much more to be gained from this kind of imagery than just bird’s-eye views of deserted landmarks.

As such, discussion in an April 29 webinar hosted by the Space Foundation and CompTIA Space Enterprise Council largely revolved around the use of geospatial data provided by satellites in monitoring the effects of the pandemic. Mark Mozena, Senior Director of Government Affairs at remote sensing company Planet, which is currently providing satellite imagery to the United Nations, gave several examples of how these pictures can show geographical changes that are indicative of the progression of a disease.

Prefacing the series of images, Mozena explained, “Geospatial data has great potential in helping not only [to] understand the spread of the current epidemic, and understand the patterns of life that may help guide decisions in the health community and elsewhere, but it also sheds insight into what the economic activities are.”

In the pre- and post-lockdown images that followed were pictures of New York City’s Central Park showing the sudden appearance of a coronavirus testing facility, indicative of the medical response there. Shadows on the roofs of oil storage containers in Oklahoma that rise and fall slightly with the level of product they contain show no movement, subtly indicating consistently full wells and thereby slowed economic activity. Likewise, images of airports with rows of airplanes parked in place indicate a high number of cancelled flights and restricted travel.

Mark Mozena shows an image of New York’s Central Park where a testing facility has appeared, describing the use of satellite imagery in tracking pandemic response during an April 29 webinar hosted by the Space Foundation and CompTIA Space Enterprise Council. Photo courtesy: Planet

Maxar Technologies is currently providing satellite imagery to support the Centers for Disease control (CDC), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in the U.S., and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) efforts globally. While Planet’s fleet of medium-resolution satellites essentially take a daily snapshot of the entire planet (with higher-resolution satellites available for specific targets), Maxar specializes in targeted imagery using some of the industry’s most impressive satellites, capable of rendering images of buildings and even people on the ground in striking detail.

About one billion of the Earth’s citizens currently live in unmapped areas, complicating the delivery of aid to people in those regions, and making this kind of imagery even more critical. If a national government needs to deliver emergency funds to affected families in such areas, they need to be able to locate them. To assist in this dilemma, Maxar donates imagery to the nonprofit organization Humanitarian OpenStreetMap (HOT), staffed by volunteers who map those areas and facilitate the delivery of aid. In such instances, satellite imagery can be overlaid on maps, allowing responders to identify routes for transporting food and medicine, or to count houses in an effort to determine how many vaccines may be needed.

And, just as satellites capture images of those unmapped areas, they also allow Earth observation companies to get a glimpse of the pandemic response in nations that have obscured or downplayed the impact of the virus. For example, images from Maxar identified where temporary hospitals have recently been built in Russia and China to accommodate more patients, and also the excavation of mass burial pits in Iran.

Naturally, the pandemic has also led to concerns about the strength of the world’s food supplies, triggering a surge in demand for data related to impacts on global industries and trade. Of immediate interest is monitoring the threat that various lockdowns and restrictions pose to food supply chains and logistics. Shipping containers are piling up in ports, truckers are enduring lengthy wait times, and meat production plants have experienced employee outbreaks that have led to closures. All of these issues raise valid questions about viable production and deliverability of goods.

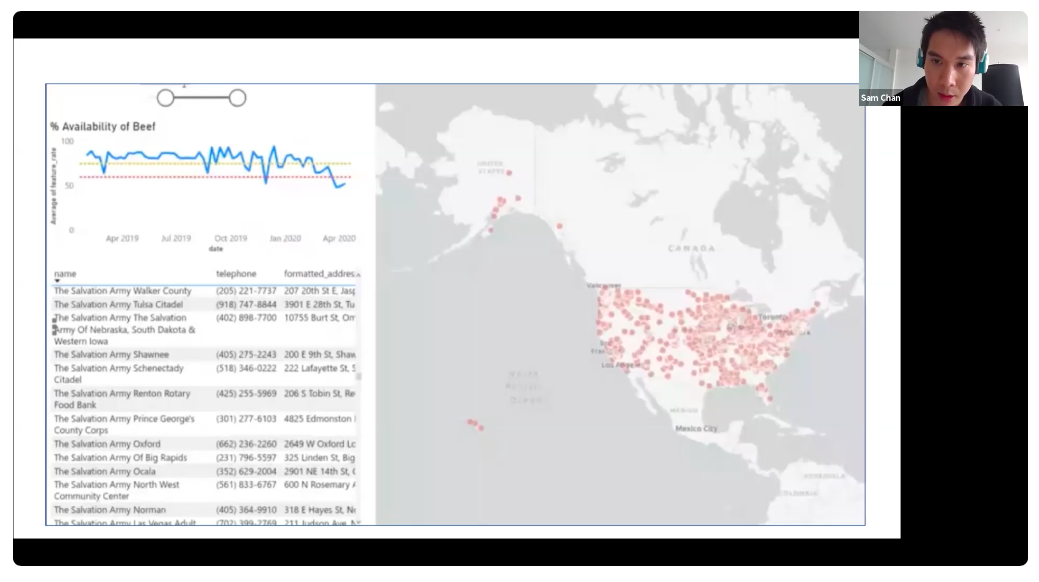

Covering this topic in the webinar were Microsoft Azure Space Lead Chirag Parikh and Senior Software Engineer Sam Chan. Although the application of this kind of data might not be the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the name Microsoft, their Azure Space service is helping by taking images and data from Planet and other partners and converting it into actionable formats.

Explaining how Azure makes sense of the sheer volume of data they receive, Parikh said, “We have a world-class group of artificial intelligence machine learning experts … to take disparate pieces of data and put together some incredible models to be able to do predictive analytics. What Azure is currently doing, is basically taking the initiatives and partnerships to connect with satellite companies across the world — defense, commercial, intelligence, civil, even nonprofit — to be able to help process, store, compute, analyze, display, and disseminate the information.”

Sam Chan demonstrates how the Microsoft Azure Space service compiles and queries geospatial data to monitor the United States’ beef supply chains during an April 29 webinar hosted by the Space Foundation and CompTIA Space Enterprise Council. Photo courtesy: Microsoft

Chan proceeded to demo Azure’s current collaboration with the U.S. National Guard called Project SALUS, in which Microsoft is working to, “solve supply chain logistic problems … supply chain excess and demand problems — basically food banks — to see who can smooth imbalances and needs of various stateside establishments during this pandemic.” The demonstration showed how Azure could use their querying systems to overlay a map of the U.S. with data about regional supplies of beef, bread, milk, or eggs, and identify areas where there may be shortages of each — or surplus supplies that could remedy shortages elsewhere.

So far this covers only the commercial side of the story, but government agencies are also taking their own approach to monitoring the effects of the pandemic from space. In March, NASA’s Earth Sciences division reached out to its employees for suggestions on how the agency could redirect its existing products and efforts to address the advancing pandemic, offering a one-time allocation of roughly $2 million to fund such efforts. High emphasis was placed on utilizing NASA satellite data to address environmental, economic, and societal impacts resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, and to help “demonstrate how NASA and related remote sensing data can characterize impacts of decisions taken or can inform public and private decision making.”

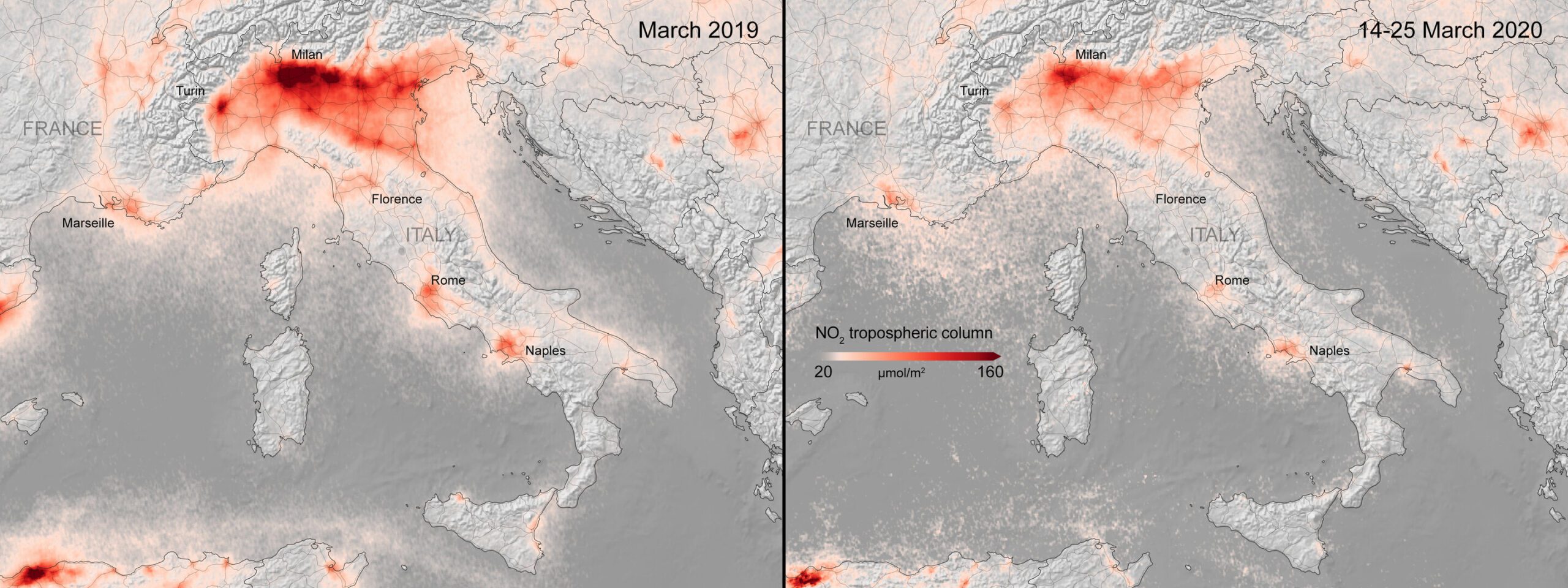

In a similar move, the European Space Agency (ESA) announced it was seeking proposals for their Space in Response to COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy by asking how affiliates could use communications, navigation, and Earth observation assets to support healthcare and research efforts in the hard-hit country, and offering selected companies access to €2.5 million in funding. In an ESA statement about the project, President of the Italian Space Agency Giorgio Saccoccia said, “We believe that, in this emergency, space, now more than ever, has to be put at the service of everyone.” Like NASA, ESA is particularly interested in better understanding the effects of human activities on the environment by studying before-and-after images that track reductions in emissions due to limits enacted on travel and industry.

Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite images show significant decreases in nitrogen dioxide concentrations over Italy, by comparing the monthly average concentrations from March 2019, to the average concentrations from March 14–25, 2020 when lockdown measures were in place. Image credit: ESA

To that end, the TROPOMI (Tropospheric Monitoring Instrument) aboard the Sentinel-5P Copernicus satellite has already observed such atmospheric changes for ESA. The instrument is currently the most accurate in capturing measurements of nitrogen dioxide as well as other particulates and industrial gases from space, and it has recorded significant decreases in fine particulate pollution. With both satellite imaging and computer models of the atmosphere, researchers have observed a 20% – 30% decrease in surface particulate matter over large swaths of China following the enactment of lockdown policies. A significant decrease in nitrogen dioxide emissions (primarily produced by traffic and industrial emissions) over Italy was also observed by the instrument.

Other orbital tools that show potential in the battle against coronavirus are Global Positioning Satellites (GPS). They are perhaps a more controversial way of fighting the spread of the virus, but by revealing the movement of people from place to place, GPS can allow researchers to follow the steps of an infected person and alert the people and places they have come in contact with.

Controversies aside, GPS-based tracking provides greater precision than asking infected individuals to retrace their steps since (and even before) they began to exhibit symptoms. As effective as GPS-based apps are in particular instances, their tracking capabilities still require some development to tackle a problem on the scale of a global pandemic, and likewise, legal structures are not fully in place to regulate the data they collect for such purposes.

Yet, the recent Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security “CARES” Act passed by Congress and signed on March 28 appears to be an effort to remedy that by making public health data surveillance a priority. Division B, Title VIII of the act states that, “…not less than $500,000,000 shall be for public health data surveillance and analytics infrastructure modernization,” and stipulates that, “[the] CDC shall report to the Committees on Appropriations of the House of Representatives and the Senate on the development of a public health surveillance and data collection system for coronavirus within 30 days of enactment of this Act.” Privacy advocates are understandably concerned about the risks of integrating health information with location-based GPS data, but it should be noted that HIPPA already permits significant information sharing in major health crisis events like the current pandemic in order to protect public health.

The GPS Block III satellite is scheduled to provide a civilian-use signal to be broadcast on the same frequency used by all current GPS users by 2022. Current legislation seeks to “modernize” the use of GPS data to track infected individuals in pandemics. Image credit: GPS.gov

Although some may find it unsettling how much information satellites in space are able to gather and relay about the daily minutia that occurs on Earth, in the midst of a pandemic that has brought the global economy to its knees and to date has claimed over 480,000 lives worldwide, the data being gathered by satellites is demonstrating remarkable capabilities in slowing the spread of the virus and enabling the delivery of aid to communities in need.

Just as dystopian satellite images in the news have revealed previously inconceivable disruptions caused by the pandemic, a silver lining is that satellite images will also show the progress we make as we emerge from quarantine measures and economic conditions improve. Furthermore, it’s a real possibility that in the wake of this virus, by demonstrating their capability to fulfill diverse, real-world needs, geospatial data companies will have instilled a broader appreciation for the value that space technologies bring to all denizens of Earth.

Said Mark Mozena in the webinar, “In my opinion, we are really just scratching the surface of what is capable with geospatial data guiding our decision-making process … as governments, also as businesses, state and local, and as individuals.”

This article is the third in a series highlighting how Space Foundation corporate partners are addressing the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. Read the first article in the series here, and the second article in the series here.